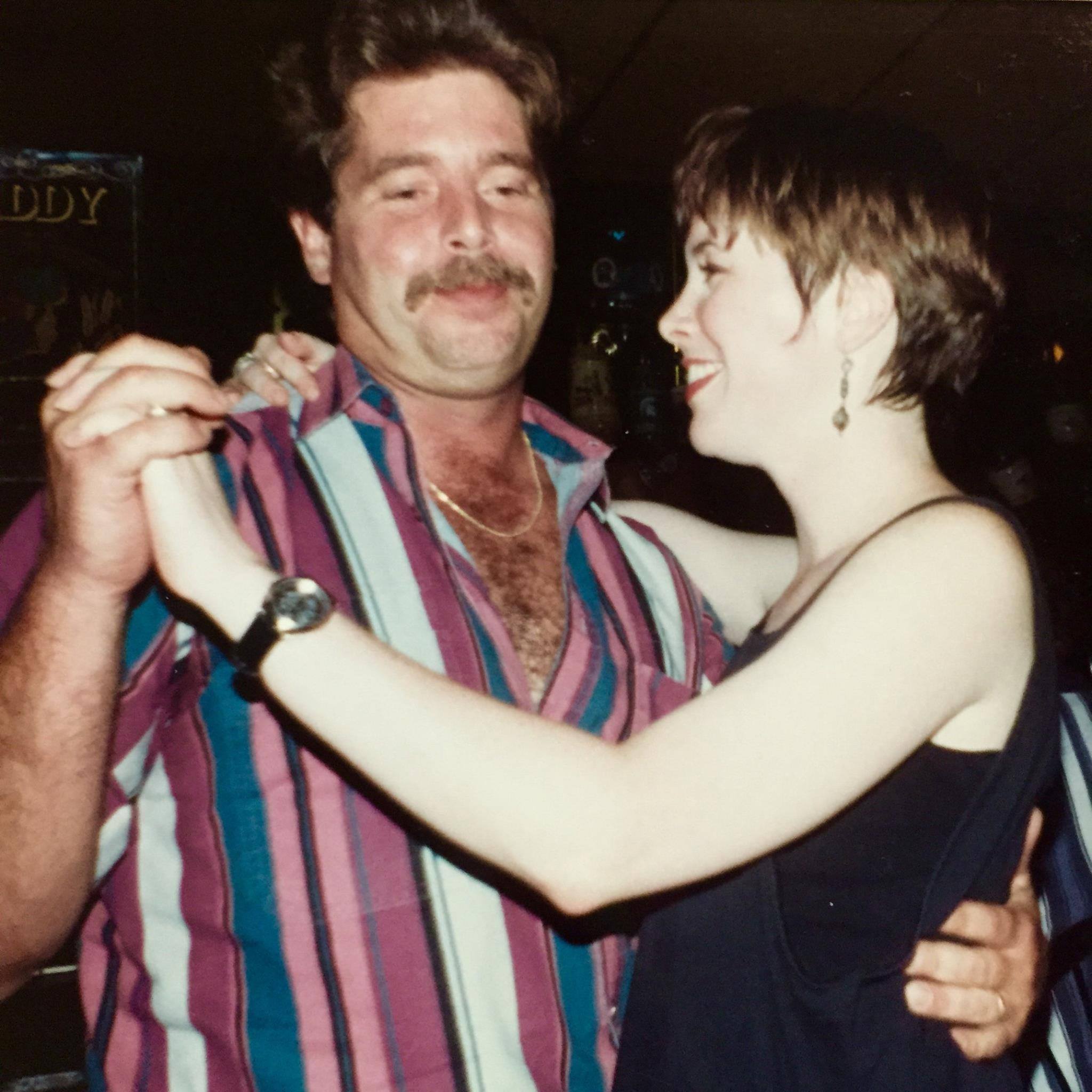

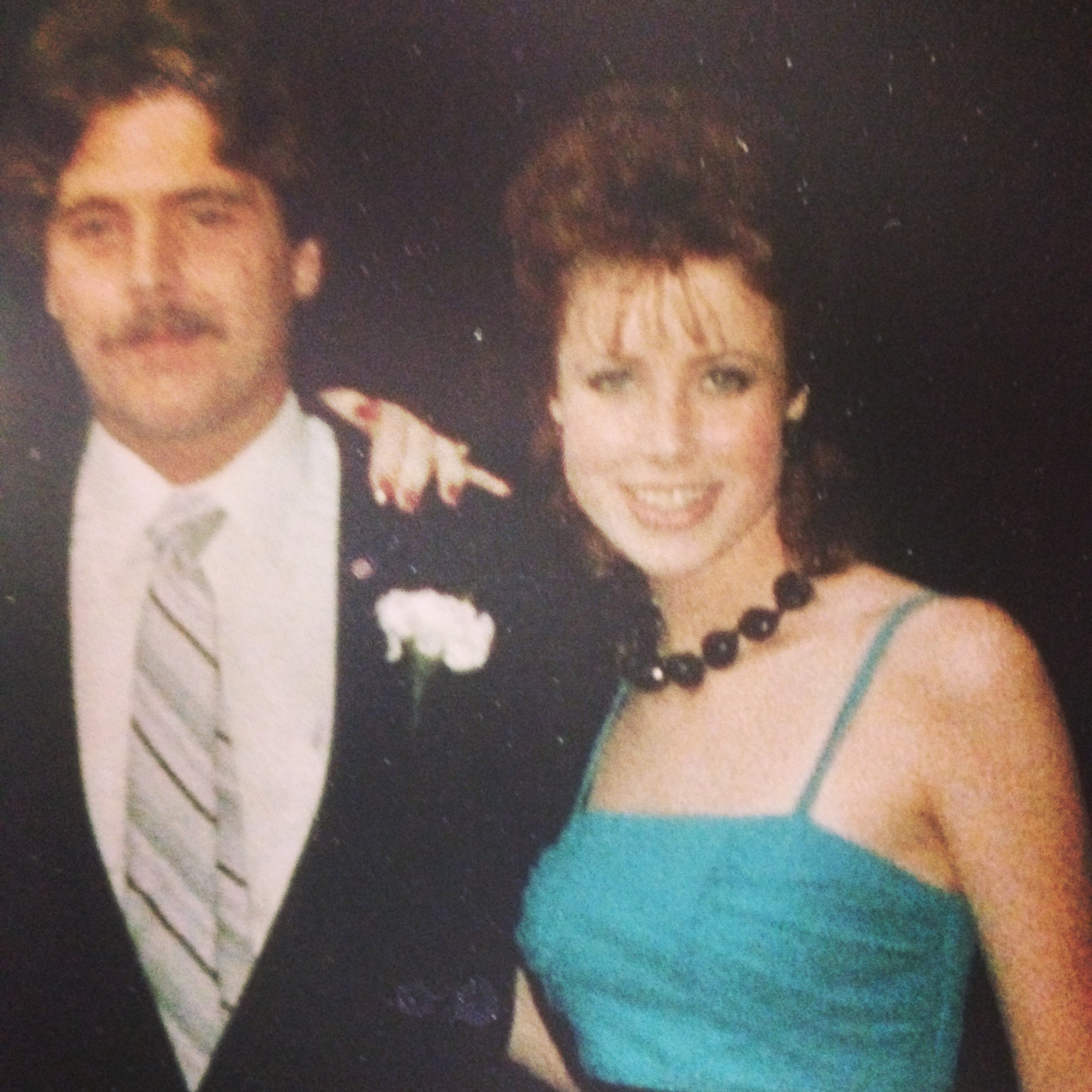

I don’t remember many people’s birthdays, but I never forget my brother’s. There were years, while I was growing up in Michigan, when we celebrated in person. There were years, after both of us had left home and settled in other parts of the country, when we caught up over the phone. And there were years, many of them, when I had no idea where he was or if he was alive. No matter the circumstances, I never forget the day he was born. Today he would have been 58.

It’s been three months since the 4 a.m. phone call from the police officer in Missouri. No good news comes at that hour, and my immediate thought was that my brother was in jail again. It did not occur to me that the news could be even worse.

“I am sorry to tell you that your brother has passed,” the officer said. I could hear the compassion and concern in his voice. He called me, he said, because I am the next of kin. I guess I am, I thought. Aside from our older sister, who had written him off years ago, it was just my brother and I. And now he was gone.

“Are you all right?” the officer asked. “Is someone there with you?” I thanked him, told him my husband was with me and ended the call. But I was not all right. Everything, every single thing, was wrong. My brother, whom I had finally reconnected with after years of estrangement, was dead. The second chance I imagined for us would never come.

When I spoke with my brother’s ex-wife later that morning, I learned he had relapsed several months ago. She wasn’t sure what he had taken. He wouldn’t tell her. But she could tell by his behavior that he had used drugs again after more than five years of being clean. She told me it had happened while she was out of town, and as we talked my guilt grew. He had called me around that time, I remembered. Busy with work, I had let the call go to voicemail and responded later via text. My message was light and pleasant. His reply was hostile and manipulative. I sensed something was wrong and decided not to respond. It was my last contact with him.

The early days of grief are filled with “what ifs.” What if I had answered the phone? What if I had been able to stop him from using again? What if our mother hadn’t died when he was 12? What if our father had been more emotionally available to him? What if he hadn’t turned to alcohol and drugs as a teenager to numb the pain and fill the emptiness? What if he had been blessed with the relatively normal upbringing I had with my aunt and uncle? The what-ifs don’t have answers, but we must ask them anyway to find our way through the pain.

Six weeks after my brother’s death, his ex-wife called to let me know the toxicology report showed no presence of drugs. My brother had died of a sudden heart attack, nothing else. He had been fighting to stay sober and had actually sought help from a drug counseling program just days before his death. It was a relief to know the relapse had been isolated, but it didn’t change the fact that he was gone.

Three months later, after a lifetime of worrying about my brother, I know he is finally at peace. I’ve let go of the guilt of not having responded to his text because I know I did it to protect my family and that he understood. I know I made the right choice, but I will always regret that my children never knew their uncle, the man behind the addiction. The kind, caring and fiercely loyal man I knew, the brother and friend I will always love, and now my guardian angel and theirs.

Happy birthday, Bill.