I met Karen shortly after the start of the race, both of us desperately bobbing and weaving to try to follow the pace group for a 4:40 finish time. It was difficult to talk as we struggled to keep sight of the red, lizard-shaped pace group sign above the sea of runners. But once the crowd thinned, we chatted easily. Karen, a thin, wiry, athletic woman with a weathered face and broad smile, told me this was her 18th marathon and then mentioned in passing that she would be 60 in three months. She immediately became my hero. As we settled into our pace, I learned she was battling a lingering cold and had chosen the 4:40 group because she wanted to start out slow (she finished the race in 4:12 the previous year), which had been my reasoning as well. I told her about the stomach issues plaguing me for the past three days and my fear they would prevent me from even reaching the start line, and we commiserated about the expected high of 80 degrees, a fluke for Portland, Oregon, which is known for cool, rainy Octobers. Unlike me, however, Karen seemed unfazed by any factors that might hinder her performance. “Every race has a story,” she said breezily.

Karen and I ran together for the first 10 miles or so, including most of a long, hot and tedious out and back through an industrial area. Around mile 11, though, the seemingly endless miles of direct sun brought me to what felt like a “mini-wall.” I struggled over another unexpected hill and began to worry about the terrain ahead. Although the race organizers bill the course as flat, that term, as I painfully learned, is relative. What a Pacific Northwesterner deems flat feels more like a constant stream of small to medium elevation changes to a Midwesterner like me. As I watched the red lizard sign disappear up ahead, I wondered if Karen, who lives in Seattle and is used to running hills, would remain with the 4:40 group. Unfortunately for me, the pace I thought would provide the easy, slow start I needed was now too fast for me to maintain.

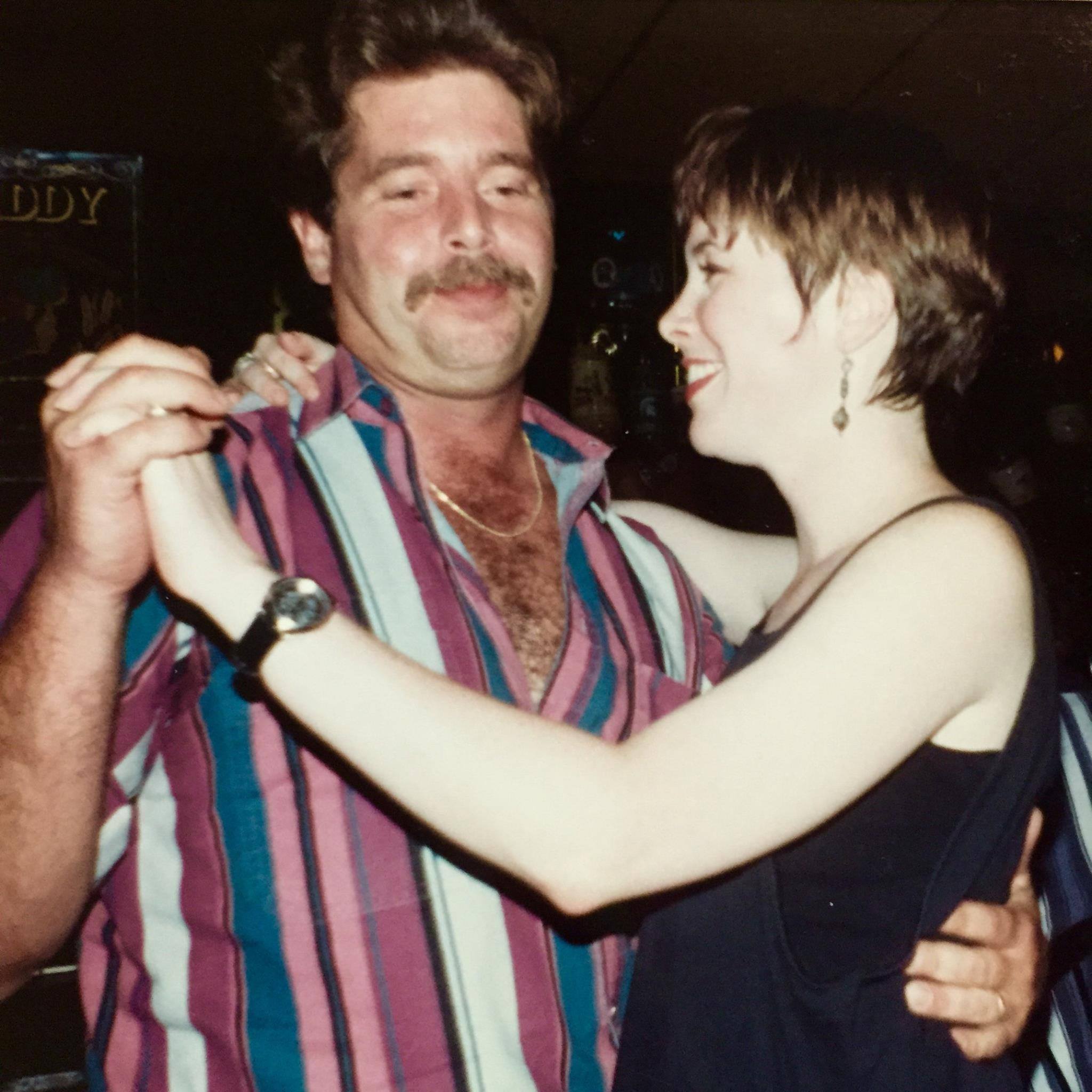

With Karen gone and no friendly chatter to distract me, the dark thoughts began to set in. I only saw my husband four times on the course, despite his valiant efforts to reach me at other points (that should be a whole other post). During the first two sightings, in the early miles when the temperature was mild and I was still with Karen, I smiled happily, waved and told him I loved him. But when I saw him at mile 12 or so, alone, in pain and doubting myself, I burst into exhausted, panicky tears. “I don’t know if I can do this,” I told him. “There are so many hills. The heat – it’s killing me.” After a teary, sweaty hug and some reassuring words, he helped me exchange the empty bottles of Gatorade on my fuel belt for the full ones in his backpack and I was on my way. Seeing him grounded me enough to continue. Even if I have to walk, I thought, I will cross that finish line.

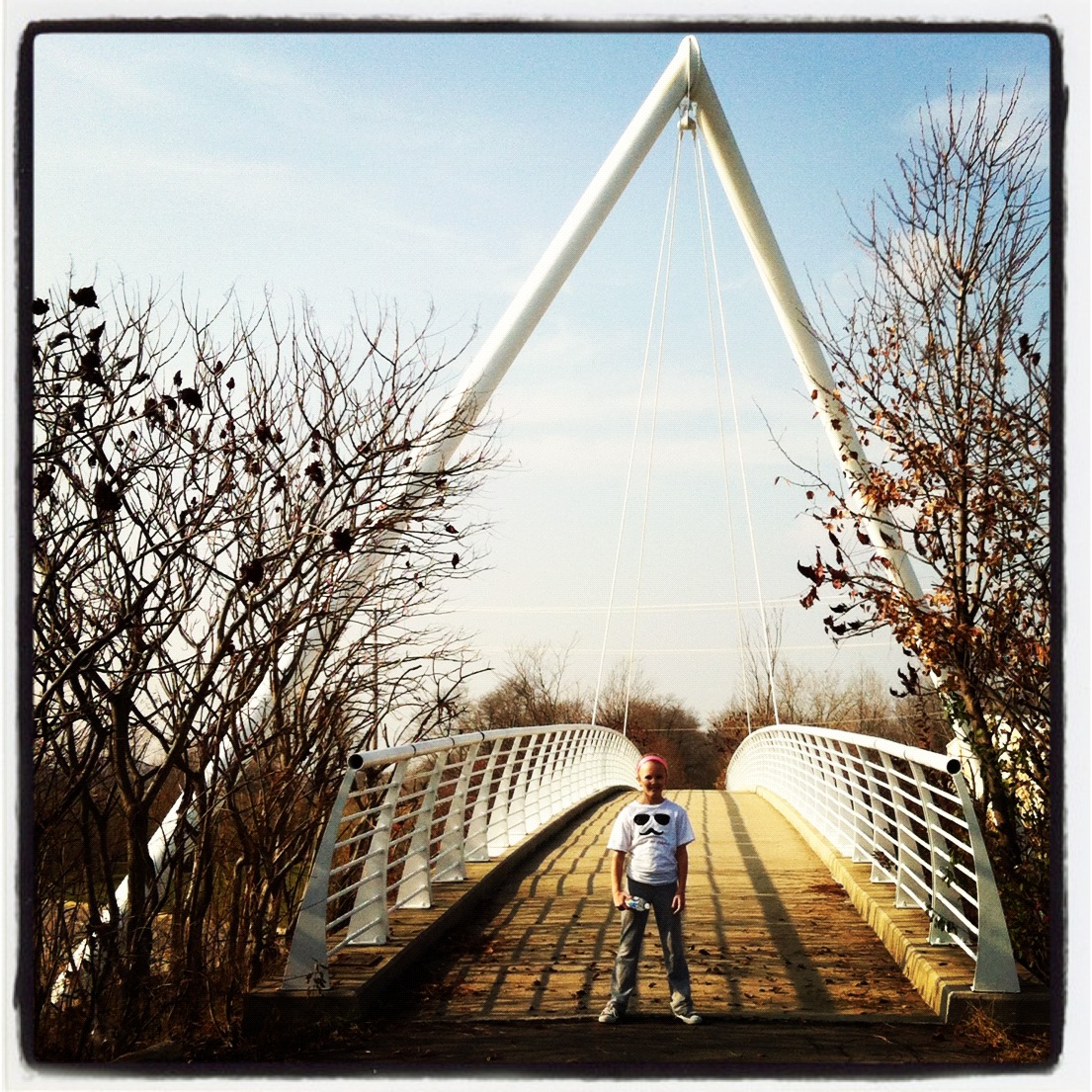

Over the next four boring, nondescript miles (at least they were pretty flat by my standards), I tried to focus on running a steady pace, but I knew what was coming. I could see it in the distance: the 2,067-foot steel suspension bridge that had been the bane of my existence for the past 20 weeks. The cramps in my feet, ankles and calves from all the elevation changes were already forcing me to stop to stretch or walk at times. St. John’s Bridge and the dramatic incline leading up to it seemed like almost insurmountable hurdles. As I approached the on ramp leading to the bridge, I noticed many runners stepping off to the side to walk. I summoned whatever shreds of stubborn pride I could and ran the incline without stopping. I thought about Karen. I wondered how her race was going, as I watched the 5:00 pace group pass me on the bridge. I barely noticed the view of fog-blanketed Mt. Hood as I plodded forward, all hopes of what I perceived as a decent finish dashed. This damn bridge is not going to take me down, I thought.

Oh, how wrong I was. The mini-wall I hit at mile 11 felt like cardboard compared with the concrete mega-wall I crashed into at the 30K mark. After my heroically stupid conquering of St. John’s Bridge, any uphill or downhill running – or walking – produced stabbing pains in my inner quadriceps. My shins and the fronts of my ankles burned, but I could stretch and walk it off. I could keep running. That didn’t work for the quad pain, and I was terrified. I began to seriously wonder if I would reach the finish line.

My husband magically appeared on the sidelines soon after I hit Wall No. 2, and I started to cry with relief the moment I saw him. “I’m really afraid I won’t finish,” I told him. “The bridge … the heat … the pain.” Once again he was my beacon, guiding me away from my fear and helping me believe in myself. “You have to think positive thoughts, Kath,” he said, hugging me tightly. I knew he was right, so I kept moving.

I don’t remember much of the last seven miles of the race. Marathon running is like childbirth in that respect: You block out the unpleasant parts afterward. My routine the rest of the way was pretty much to just run until the stabbing pain in my inner quads and the cramps in my shins, ankles and feet overwhelmed me, stop briefly to walk or stretch, and then push onward. The hills kept coming; there was even another damn bridge toward the end; and when I finally saw the finish line, my exact words were, “It’s about f—— time!” Yes, I said that out loud. Somehow I managed a negative split in the last mile. I think it was just because I wanted it to be over so badly.

I cried yet again when I saw my husband searching the crowd for me in the reunion area, happy to find him and overjoyed to be done. “You would have hated that race,” I told him. I wasn’t just trying to make him feel better about not being able to run it due to an injury. At that point, I did hate the race. It was nothing like what I expected: the decidedly not flat terrain, the brutal heat, the boring course. Even the smattering of crowd support hadn’t helped. A stranger half-heartedly yelling, “Go, Kathleen,” doesn’t do much to bolster your morale when your legs are searing with pain and you’re afraid you may not make it to the finish line – at least it didn’t for me.

When I started to tell him about Karen, whom I never saw again unfortunately, I began to view things differently. She was right: Every race does have a story. While mine was not pretty, it did teach me some valuable lessons about what not to do when training for a marathon. For one thing, don’t go into the race without a true understanding of the terrain (again, “flat” is a relative term depending on where you live). Also, don’t discount the importance of hill work (I have since vowed to incorporate a hill run into my schedule every week). And finally, the most important thing I learned: Don’t have rigid expectations (if 4:40 was my planned starting pace for a cool race, 5:00 may have been a better place to begin on such a hot day).

Best beer I ever tasted. I have never been so happy to finish a race.

After spending Monday shopping, eating and drinking our way through Portland (what a great city!), we headed back to Chicago on Tuesday. Despite my relatively good spirits after the race, the post-marathon depression hit me pretty hard the following morning as I prepared to go home and back to reality. Nothing had gone as planned, and I felt defeated and demoralized. After 20 weeks of hard work – I missed only one run and that was during the taper because of hamstring pain – I knew I was capable of so much more. My 20-miler had been so strong: 10:26 pace, mostly negative splits. I felt great afterward and even ran five miles the next day. Why had everything gone so miserably wrong during the actual race?

On the flight home, I wound up sitting next to another Portland Marathon finisher. After noticing his marathon shirt, I told him I had run it as well and asked how his race went. He told an all-too-familiar tale: The heat and hills exhausted him, he felt pain in muscles he didn’t know he had, his time was way off his goal, and he struggled just to finish. I am an almost 47-year-old mom with a beyond non-athletic build who never participated in sports and could not even run around the block until I was almost 40. He, meanwhile, is an incredibly fit 28-year-old who played college and professional basketball in France. But somehow, as crazy as it may seem, we shared the same story. You have no idea how much better that made me feel. Thank you, serendipity. I needed that.

In the five days since the race, I have run the gamut of emotions about my marathon experience finally coming to an end: joy, sadness, denial and acceptance. I seriously contemplated running another marathon in a month (that would be the denial phase) to prove to myself that I could improve my time, and I even managed to get my husband on board with the plan. Thankfully, I came to my senses, and the words of veteran marathoner Karen helped me. There will be other races. I have more stories to tell. The important thing is that I finished my second marathon and even eked out a tiny PR. I can view it as a failure because I didn’t meet the expectations I set for myself, or I can treat it as a lesson and do some things differently next time. I choose the latter. In fact, I’m already planning next year’s race schedule.

***

Thank you to everyone who followed my training journey over the past five months, listened to my ceaseless and obsessive ramblings, and lent me support along the way. You all made me feel like a winner.