This morning I dropped off my son for his first day of finals as a high school freshman. I know he cares about his grades, and he says he studied. But how he does is entirely up to him. I can’t take the tests for him. Heck, I would probably bring down his GPA if I attempted the honor’s geometry exam. I can’t talk to the English teacher who he feels is being unfair. Well, I could. But I’m not going to. Sometimes mama bear has to back off. Today is one of those times.

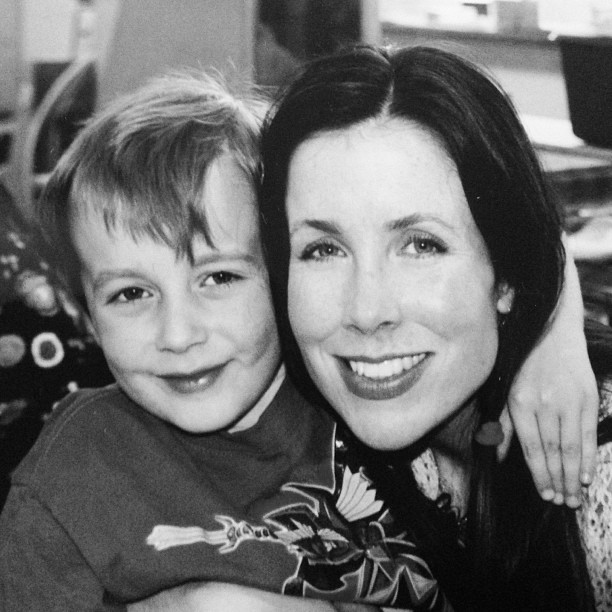

I will admit to having been an overbearing, overprotective, borderline obsessive-compulsive parent when my son was small. He was my first child, I had no idea what I was doing, and my biggest fear was of doing the wrong thing or, worse yet, not doing enough. I anally retentively organized his Lego blocks, dinosaurs and Matchbox cars into labeled bins. Each night, as we cleaned up the playroom, I followed closely behind him, sorting through the toys he carelessly tossed into the wrong bins. I made sure the Spider-Man puzzle wasn’t missing any pieces and all the Imaginext figures were on board their pirate ship. I maintained the order in our little universe because I could and thought I should.

But what if I hadn’t picked up all the pieces and erased every mistake? Would it really have mattered if a Lincoln Log turned up in the Thomas the Tank Engine bin?

I look back and cringe at my perfectionist self in those early years. I micromanaged every aspect of my son’s day based on all the parenting books I read. I knew what to expect when I was expecting, during my son’s first year and when he was a toddler. I kept careful track of his progress, visiting the pediatrician more times than I care to admit when he didn’t fall within the range of what the books described as “normal.” I knew that healthy sleep habits make a happy child — thanks to the similarly titled book by Dr. Marc Weissbluth, which I read multiple times — and I rigidly enforced nap and bed times to the point of turning down playdates and leaving parties early. My parenting bibles gave me a sense of control amid the chaos of the early years of being a first-time mother.

When my son started kindergarten, I redirected my need for control to my own life and went back to work part time. Having a focus outside the house, even though I worked from home, helped me regain my sanity, and I think it also benefited my second child. I enrolled her in preschool five days a week at age 3. In the afternoons, when she was home, I sometimes had to conduct an interview or finish an article. She colored in my office, watched a video or played by herself in her room. My work deadlines kept me from obsessing over missing puzzle pieces or misplaced toys. My daughter was, and is, confident, assertive and independent, and I think that has something to do with me being forced to back off with my mama bear ways.

It’s still there, though, that urge to step in and fix things, especially with my son because I did it for so many years. After I dropped him off this morning, I thought about calling the English teacher with whom he is struggling. Would it be so bad for me to interfere — just a little? Yes, it would. I have to let him try to work out this problem on his own first because soon enough he will be heading off to college, and mama bear isn’t allowed there — or at least shouldn’t be.

Mama bear is backing off today, but that doesn’t mean I’m not worried about my son. It doesn’t mean I don’t love him. It means that I know if I keep cleaning up his messes and erasing his mistakes, he will never learn to do it for himself. Sometimes doing nothing is harder than doing something. Today is one of those times.